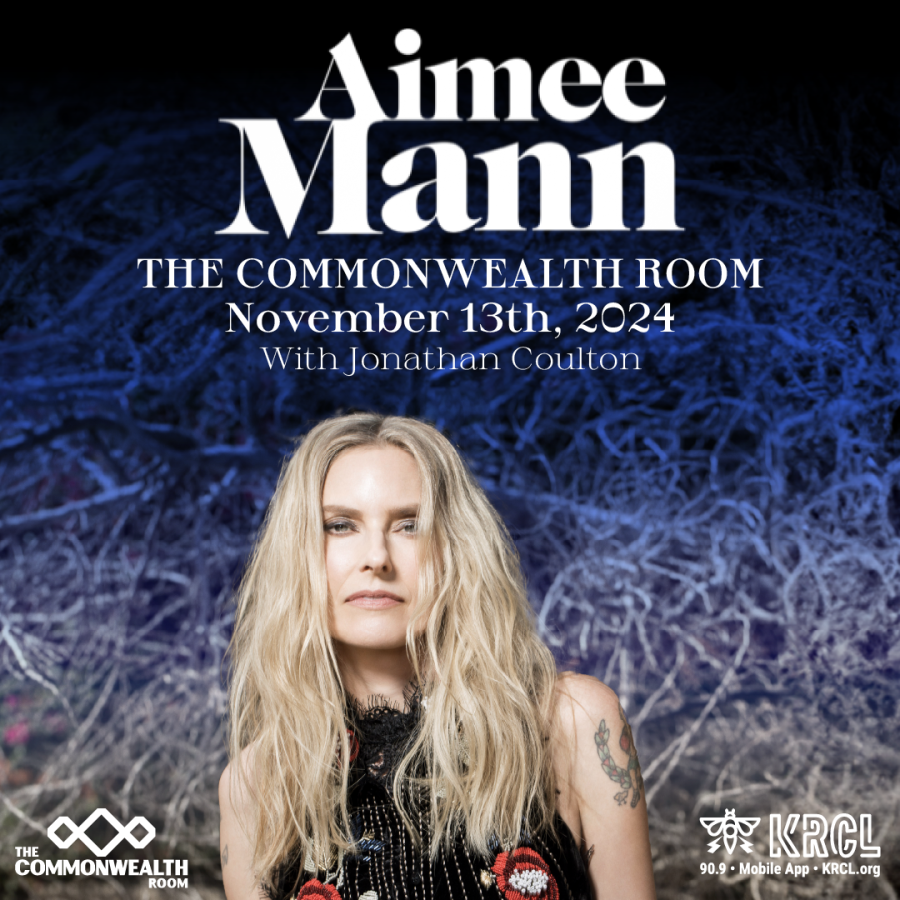

Aimee Mann

- Doors

- 7pm

- Show

- 8pm

- Ages

- 21+

Description

Aimee Mann

Aimee Mann’s first new solo album in five years arrives with a title loaded with possible meanings and intent. For her, its provocative branding comes down to something akin to truth in advertising. “It came from a friend of mine asking me what the record was about,” she explains. “And I said, ‘Oh, you know me — the usual songs about mental illness.’ He said, ‘You should call it Mental Illness!’ I said, ‘I think I will.’” And thus, over the course of a few short seconds, was a classic album title born. “I always probably have a little bit of gallows humor,” Mann says, “and I would hope that people see there’s a little bit of that interspersed in there. I mean, calling it Mental Illnessmakes me laugh, because it is true, but it’s so blunt that it’s funny.”

What kind of pre-existing conditions come with Mental Illness? Some fans will see the album as a return to more musically familiar territory. After a couple of records that saw Mann leaning toward the rockier side (her last solo album, 2012’s Charmer, followed by her 2014 duo project with Ted Leo, The Both), this new one finds the woman who gave the world “Wise Up” again deciding to slow up. If you fell in love with earlier albums like Bachelor No. 2 and the Magnolia soundtrack, the gorgeous melodies and deliberate gait of this return to contemplative form will seem deliciously familiar.

At the same time, the arrangements mark a break from anything she’s done before, even those aforementioned landmark albums. Gone are the Mellotrons and some of the other distinctive signature sounds of yore. Although there are some electric instruments and occasional drums in the mix, Mental Illness is built for really the first time in her career around acoustic guitar and piano… and then, in another first, augmented astoundingly by starkly beautiful string arrangements. Spines will tingle, and softness and bluntness will find a happy marriage in songs that make up in haunting splendor for whatever they might lack in ebullience.

The album’s rich, incisive, and occasionally wry melancholia started with a mission statement of sorts, prompted by Mann’s own slightly tongue-in-cheek take on her own image. “I assume the brief on me is that people think that I write these really depressing songs,” Mann says. “I don’t know — people may have a different viewpoint — but that’s my own interpretation of the cliché about me. So if they thought that my songs were very down-tempo, very depressing, very sad, and very acoustic, I just gave myself permission to write the saddest, slowest, most acoustic, if-they’re-all-waltzes-so-be-it record I could,” she laughs.

That’s admittedly a pendulum swing away from Charmer and The Both, which found her gravitating toward the sounds or energy level associated with her tenure in ‘Til Tuesday in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. “Since the last project was with Ted Leo, and he certainly has a lot of classic rock, post-punk influences, I tried to meet him in the middle,” she says. “Touring and playing in smaller rock clubs with The Both as a trio, with me playing bass, was a real rock band experience.” Now, on the heels of delivering fans a power trio experience, “I think they might be ready for something super-sad and soft,” Mann says, hinting at a smile as she considers the path that brought her to being a one-woman delivery system for mellow gold in 2017.

The S-word, obviously, is no pejorative here. “I was listening to a lot of really soft ‘70s rock, like Bread and Dan Fogelberg,” Mann points out, offering up a couple of acts so far off the indie cred scale they seem like prime candidates for indie cred. (Completely coincidentally, she was recently asked to cover a Carpenters hit for the soundtrack to Martin Scorsese’s ‘70s-set HBO series, Vinyl.) But “there were other touchstones that we kept in mind,” a key one possibly being longtime producer Paul Bryan’s love for Nick Drake. “It always takes its own form. I just wanted to have finger-picky stuff, kind of like Leonard Cohen back in the folk-rock days. I haven’t ever made a record this stripped down before. Some drums wound up on there here and there, but I really tried to rein it in.”

Despite her best efforts to hold back the tide of extraneous instrumentation, there was an extravagance Mann couldn’t pass up, as the string arrangements Bryan was writing for a couple of songs proved so lovely that they began extending them to more of the tracks. The end result is “not as simple as my original concept,” she says, “but it’s just really hard to go into the studio and not have ideas for things, and it’s so fun and interesting to record real strings. That definitely makes things bigger and more fleshed out, but I hope that the basic acoustic elements still come across as distinct and simple.”

Besides Bryan, the players include other familiar cohorts, like Jonathan Coulton, who has his own album coming on Mann’s Superego label, and who’ll be her opening act on tour this year, doing some of the more detailed finger-picking. Other musicians include Jay Bellerose on drums, Jamie Edwards on piano, John Roderick as a co-writer, and erstwhile duet partner Leo as a background singer.

She has a little to live up to with Mental Illness, having long since transitioned from an MTV staple in her Til Tuesday years to becoming known as “one of the finest songwriters of her generation,” as the New York Times proclaimed her. NPR Music named her “one of the top 10 living songwriters” alongside the likes of Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. Her last solo album won her some of the best reviews of a storied career. Paste opined: “She is innately tuned into our fragility and resilience. Like the Velvet Underground’s Nico, she’s our mirror. Through her songs, she reflects life as it so often is—a contorted, gasping mess—but somehow she still finds beauty in its imperfection.” Britain’s Independent called Charmer “another sweet viper's bite of post-Freudian dyspepsia from the singer-songwriter who loves to mistrust.” Or, as the New York Times wrote, “The sugarcoated poison pill is a reliable device for Aimee Mann, a singer-songwriter given to ravaging implication and dispassionate affect... That it all goes down so easily seems like a sneaky way to make a point.” Charmed, they’re sure.

Validation came not just from the Grammys, but the Oscars, as she earned Academy Award as well as Golden Globe nominations for best original song for “Save Me,” part of an acclaimed song score for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia that ensured her voice would carry to entirely new audiences. Before her contributions to Magnolia, she made a quick, quirky screen appearance in The Big Lebowski as a German nihilist/kidnapper. Further up the typecasting scale, she played herself — albeit, a fictionalized, comically down-on-her-luck version of herself — on a classic Season 1 episode of her friend Fred Armisen’s series, Portlandia. She’s witty enough to have been named one of The Huffington Post’s “13 Funny Musicians You Should Be Following On Twitter” and serious enough to have been invited to perform for President Obama and the First Lady, sharing the bill with Common at a private, poetry-themed White House gig.

Speaking of presidents… In 2016, when Dave Eggers started a project to enlist 30 artists to write 30 songs about Donald Trump prior to the election, the first person he enlisted was Mann, who contributed an attention-grabbing tune with the chorus, “I don’t want this job/My God, can’t you tell/I’m unwell?”

After that, you might want to jump to the conclusion that an album with a title like Mental Illness might have a political component. It’s not quite that topical, but really represents classic Mann, in songs that mostly describe the obsessions and moderately aberrant behavioral patterns that have been the hallmark of thwarted romance from time immemorial. A few do deal with run-ins she and her friends have had with liars pathological enough that they might live up to the clinical condition of the title.

“There’s still a stigma to a certain kind of mental illness,” she says. “I feel like it’s a world I’m kind of familiar with, not only from my own experience, but just people I know who are just trying to work out their stuff. I certainly do think everybody’s got their thing. I wouldn’t go so far as to say everybody’s mentally ill. I’ve seen a lot of talk about Trump having narcissistic personality disorder, which I one-hundred-percent agree with, but I don’t even know if that qualifies as a mental illness. I think another way to look at that is, people are trapped in compulsive behavior. There are definitely a couple of songs on the album about a person I knew who probably is a sociopath, but even then, I’ve kind of realized that sociopathy is a combination of things. And I’m very fascinated by codependency, or people who enable other people’s bad behavior or addictions — I mean, I’m certainly no stranger to it.”

Not every song on the album is about such alarming behavior. The first single, “Goose Snow Cone,” may be its sweetest, least barbed, and most autobiographical, simply because it describes feeling disconnected out as a touring artist on the road, as accentuated by photos of a certain someone back home. "I was in Ireland and it was snowing, at the end of a tour, and I was feeling exhausted and homesick,” explains Mann. "My friends have this cat named Goose, and they posted a picture of Goose’s little face on Instagram — she’s got white fur, and it really looked like a snowcone ball. So I start writing this song. It’s really more about being homesick and lonely than it is about the cute little kitty, but that’s the way it came out.”

The sickness gets less benign on other tracks. Being one of the songs about a sociopath that crossed her path, “Lies of Summer” is about the not-so-instant replay you might do in your head “once you realize that somebody’s a pathological liar. Then you scroll back through all the encounters that have just been slightly off, and you see those in a different light.” The song “Rollercoasters” describes “the feeling of being addicted to extreme emotional states — high is great, but low will do when high is not present—and how easy it is to lose yourself in drama because it’s so perfectly distracting.” “Knock It Off” is an advisory to a guy whose lying caused a breakup, but who the lyrics describe as “just stand(ing) there on her front lawn,” like Lloyd Dobler, but not as cute. “That intersects with what people think of it as the sort of cinematic/romantic moment, hoisting the boom box over your head. It’s crazy behavior! It’s not taking no for an answer, which is not a great trait in a relationship.”

The theme of not being able to break bad patterns pops up recurringly in the lyrics of Mental Illness. Isn’t the clichéd meaning of insanity doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different results? It’s the human condition, to an extent, but Mann is more hopeful about breaking these cycles than some of the still-fogged-in narrators of her songs, like the woman in the final number, “Poor Judge,” who “can see a light on… calling me back to the same mistake.”

“The general topic of mental illness is something I’m interested in because there are ways in which it’s like addiction, in that parts of it are compulsive and seem beyond your control,” says Mann. “But there’s always something that you can do or try to help yourself to better the situation, even if it’s just taking your medicine or exercising if you’re depressed. And I guess I find that encouraging, even if it’s a small chink in that armor. You know, I never think it’s completely hopeless. And I think that’s the good news about personal responsibility — that there’s always something you can control.”

And if her songs aren’t nearly so solution-oriented as all that? After all, the song “Simple Fix” suggests there’s no such thing, with Mann sounding a bit fatalistic when she describes us all as “babies passing for adults/Who’ve loaded up their catapults/And can’t believe the end results/So here we go again.” But, says Mann, “I think that the most interesting point at which is a song gets written is the lament before the solution is either thought of or implemented. The hope in the songs is probably just in talking about it. Sometimes there’s a benefit in just saying, ‘I give up, I can’t go on,’ and then having that moment before then you go on.

Some might think Mann just a little bit crazy — for lack of a more sensitive word — for making a record this soft-spoken in a climate where everyone has to yell ever-louder to get attention. Or for almost boasting about its anti-cheeriness at a time when the social clock of half the nation is already stuck at approximately half-past-wristcutting. But to her, it’s really upbeat, if only to help listeners feel like they’ve found their tribe: “I think people like to think somebody understands the more difficult things that they go through.”

And as for the literally downbeat aspects of putting out an album this slow and stolidly beautiful in the age of BPM and clanging: “Part of that is like, why not? Because there’s a certain liberated feeling — if the death of the music business is nearly complete, you can really do whatever the fuck you want!” Saner words may never have been spoken.

Jonathan Coulton

In 2004, Jonathan Coulton was a techno-utopian. He had a job coding software, but for fun, he’d written some quirky pop songs—and in a bit of skipping-stone serendipity, he got invited to play them at a tech conference. When he sang the rhapsodic bridge of “Mandelbrot Set”—a gorgeously articulated math equation—the audience jumped to their feet, clapping and screaming. Afterwards, Coulton watched a speech by Lawrence Lessig, in which the Harvard Law Professor described the Creative Commons: shared art, uploaded online, liberated from traditional copyright. When Coulton walked out into the cold Maine sunshine, he remembers, “It was like my head was on fire. I was like, holy shit, something is happening!” Suddenly, anyone could publish music. Between HTML, MP3s, and Paypal, you could build your own label. Podcasts were radio shows. The internet had just begun to blink fully awake, but already it was a tangle of creativity, turning strangers into a community.

Growing up in rural Connecticut, the son of a lawyer and a schoolteacher, Coulton had always been a song geek. He played guitar and recorded originals on a cassette 4-track. He was a regular at midnight-movie shows of Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” (over his bed, he draped a silky fan-tapestry, printed with bricks). And he dug the more humane, story-based breeds of pop: The Beatles, Billy Joel, Steely Dan, Crowded House. At Yale, he sang with The Whiffenpoofs. But once he’d graduated, he found that making music was a grind: in 1990s New York, it was all about pasting flyers and begging friends to pay for two shitty cocktails. Instead, Coulton got a dot-com gig, building databases. Now, he realized, there was a whole new way to reach an audience. At 34, married, with a newborn daughter, Coulton quit his day job. In 2005, he launched the Thing-A-Week Project, sparking a burst of productivity that turned him into a cult figure—online-famous, Version 1.0. Along the way, he won a reputation as “the internet music-business guy,” an artist who communicated directly with his audience, having circumvented the kludgy, crumbling music industry.

This was the era when, like many of his most deranged super-fans, I first discovered Coulton’s music. His songs blew my tiny mind: they were equally funny and profound, full of wordplay that kept tilting, fast, into deeper emotion. He had an abiding love of character, a lyrical gift that reminded me of They Might Be Giants and Paul Simon, Elvis Costello and Aimee Mann. A lot of those songs were also about zombies and giant squids, a nerdy streak that might, in less-skilled hands, have felt gimmicky. But Coulton’s appeal wasn’t about comic book references (I’d barely read any), but a rare, intimate insight into a newly mediated landscape. He had a few specialities, among them a raft of songs about nice-guy pathologies, like “The Future Soon,” about a resentful teen nerd, and “Skullcrusher Mountain,” from a supervillain’s POV. But when Coulton told a story about Bigfoot, it was about a brutally hot one-night stand. When he sang about a noisy shop vac, it was really about loneliness and marriage. If he had a mission, it was to treat geek culture not as something exotic or silly, but home-like, familiar: it was what we were all soaking in.

A decade passed. The world changed—and the internet with it. “I read Omni Magazine. I read Wired Magazine. I knew the internet was going to save us, because it was going to connect us and free us,” says Coulton. “It didn’t happen that way.” Coulton’s latest album, “Solid State,” is, like so many breakthrough albums, the product of a raging personal crisis—one that is equally about making music and living online, getting older, and worrying about the apocalypse. A concept album about digital dystopia, it’s Coulton’s warped meditation on the ugly ways the internet has morphed since 2004. At the same time, it’s a musical homage to his earliest Pink Floyd fanhood, a rock-opera about artificial intelligence. It’s a worried album by a man hunting for a way to stay hopeful.

Coulton’s last album, “Artificial Heart,” from 2011, was itself a jump away from explicit storytelling, a ferocious, elliptical rock-and-roll album made in collaboration with John Flansburgh of “They Might Be Giants.” When that was done, Coulton felt like he’d never write a song again. As a hard reboot, he took an electronic music course in lower Manhattan, one that was dominated by 24-year-olds hammering together surreal tracks of dance music. Their waves of sonic mush and swooping arpeggios suggested a new path in. Coulton began experimenting with his sound, and those knob-tweaking games evolved, gradually, into a coded memoir about his own ambivalence about the future, soon.

The title track, “Solid State,” which brackets the album, is, Coulton jokes over cocktails in Brooklyn, “a hopeful look at how the internet sucks.” On the one hand, Coulton says, the “solid state” is what our culture used to be, pre-web: unmoving, stable, but also essentially non-communicative. The digital age changed us, fast: ”Now we can hear each other and it’s terrible.” But the metaphor is also about the relationship between old-fashioned vacuum tubes—with their organic distortion, so hard to control—and modern solid-state electronics, which gave us both digital amps and the blunt force of mini-computers. Digital models are more efficient and powerful, but they are also icier, more brittle. “If the internet is this cold digital structure, we are the distortion that gives it warmth.” Or as the song itself puts it, “It’s all messed up, it’s better that way.”

In a linked graphic novel written by Matt Fraction and drawn by Albert Monteys, the songs of “Solid State” narrate a trippy epic, a psychedelic, futuristic narrative about two men whose fates are linked over time (and who are both, as it happens, named Bob) and the God-like artificial intelligence that both protects and abandons them. It’s a Neal Stephenson/Ray Kurzweil/Kevin Kelly-inflected fable that is located at the end of the world, much of it deep inside a city that has been sedated by what Coulton calls “nicey-nice fascism”—locked-in, medicated, machine-run—and which is ringed by a raw, ruined apocalyptic landscape. The graphic novel is a story about how we got there from here.

Yet the songs work individually, too. “All This Time” is a rebel song from deep inside a zoned-out, medicated mindset: “Reds for focus blues to not get upset/Wasters and complainers get what they get/All eyes watching, no one’s noticed me yet?” “Brave,” a dark extension of those early nice-guy songs, is the voice of a shit-posting troll straight out of 8Chan: “When I torch the place/And cover up my face/That will make me brave.” “Square Things,” constructed from a whole-tone scale, evokes the spinning cubes of Windows-style software, with double-edged lines like “Everyone choose a side.” “Ball and Chain” is a marriage song. So is “Tattoo,” which Coulton describes as “a metaphor for a permanent choice, a thing that gets made and gradually degrades—and about finding beauty in that change.” With its eerie Beatles-meets-lullaby vibe, “Ordinary Man” sneaks up on an unsettling dystopian taunt: “You say no one tells you the ending/But it ends this way.” The biting “Don’t Feed The Trolls” is about the double-bind of the outrage economy: “Dance like they’re watching you/Because they are watching you.” The Oasis-tinged “Sunshine” is the upbeat death anthem of an apocalyptic survivor; and there are some erotic-trance songs in the mix, too, experimental voices from deep inside the POV of a loving, ever-evolving God-like artificial-intelligence, a strange creature who has moved past humanity but still craves intimacy with it (“I Want You All to Myself”).

Musically, these songs have a pared-down anthemic force very different from the chord-heavy guitar-pop that made Coulton famous. Coulton created them while working, in close collaboration with his producer Christian Cassan, from his home in Gowanus, Brooklyn, often composing “in the box.” He tweaked knobs for inspiration, building waves of drone and jangle and hum that feel a bit like a digital hymn. And yet these are also dialectical songs by design: they’re solid-state anthems that are meant to question — and maybe to mourn — the method of their own production.

As it builds, “Solid State” flips the script on some of Coulton’s oldest obsessions: rather than dwell on our responses to the internet, these songs also wonder what the internet thinks (and feels) about us. They’re stories about a poisoned utopia, in which the endless choices might all seem bad: staying connected and cutting yourself off; being known and being anonymous; narcotized safety and feel-everything risk. As the reprise of “Solid State” suggests, this is an album about a life that’s beautiful precisely because the end isn’t so hard to imagine, about a shadow that can’t be separated from the cold sunshine that he walked into back in 2004: “A pretty sweet ride, as long as you can hold on/Here right now. And gone when it’s gone.”

-Emily Nussbaum

THE STATE ROOM

638 South State Street

Salt Lake City, Utah 84111

800-501-2885

Box@TSRPresents.com

THE COMMONWEALTH ROOM

195 West 2100 South

South Salt Lake, Utah 84115

800-501-2885

Box@TSRPresents.com

THE STATE ROOM PRESENTS

DEER VALLEY

LIVE AT THE ECCLES

FORT DESOLATION

OTHER ROOMS

Tickets online at AXS.com

In person at Graywhale

Box office open show nights